|

|

(Author’s note: I grew up

in North York, Ontario, watching the show The Friendly Giant, 15

minutes away from the Don Mills home of its creator and star, Robert Homme.

I never discovered this until meeting him a number of years before

his death, when he lived in Grafton, Ontario and I lived, coincidentally,

15 minutes away near Centreton. This article is the result of a series

of friendly visits with Homme and his wife, Esther.)

When the song Early One Morning is heard today, many child-at-hearts

will immediately recall those mellifluous lilting notes as they were

once played: on a recorder as a castle came into view. Perhaps the

misty memory of a slowly lowering drawbridge comes into focus, and

a kindly voice invites you to “Look up …way up ….” Once

across the threshold, however, you entered a world far removed from

a mediaeval fairy tale in which knight errants saved swooning princesses

from Shrekesque ogres ad nauseam. No other children’s television

program then or now could boast such an eclectic ensemble of cheeky

animal puppets - a distinctively coloured harmonica-playing giraffe,

a perky little polka-dot rooster, and finely sculpted Steiff porcelain

cats and racoons. Add one educated giant to the animal menagerie,

carefully chosen classical and jazz music, and literature with educational

and

moral values, and it became an artistic mix that children as well

as adults found themselves choosing to watch over more routine fare.

So, pull up that chair. Or perhaps you’d like to curl up in

that one over there? Imagine that a gilt-edged volume is taken down

from the shelf and opened

gently. And hush now, because the storybook life of a television giant had

a beginning. And once upon a time...

|

All photos © copyright L. Chrystal Dmitrovic |

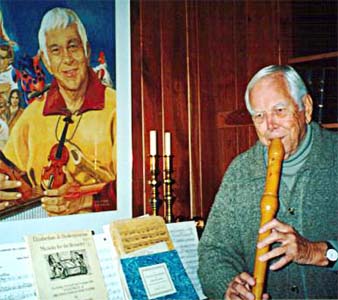

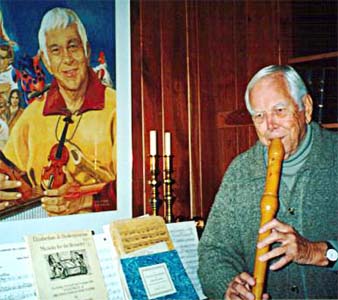

| In the large

basement office/den of his Grafton, Ontario home, Robert

Homme’s

days were always full: practicing his recorder and preparing

for public appearances, recording

audio projects, or working on his memoirs. |

Robert Mandt Homme grew up in Stoughton, Wisconsin, a small town near Madison

surrounded by checkerboard farms. By junior high school, he’d latched onto

the clarinet, and played in dance bands to help pay for two years of college.

Volunteering before being called up on draft during WWII, one of his commissions

was to psychologically determine what position recruits were best suited for.

After numerous transfers around the U.S. due to the nature of his assignment,

he was deployed to Guam where he was given opportunity to display a natural talent

for sophisticated jazz, performing on clarinet and saxophone in a band at officers’ dances.

(By war’s end, he reached the rank of Army Air Corps staff sergeant.)

His longtime love of music then led him away from conventional post-war employment

toward a more creatively inclined future.

Homme’s true media career began a number of years later with his arrival

at the oldest U.S. educational radio station, WHA based at the University of

Wisconsin. As host of the children’s show, Just for Fun, he had little

inkling that a radio format would one day lay the foundation for his signature

TV series, The Friendly Giant. He recalled, “Unlike other children’s

programming on radio, mine was very quiet. Each segment was basically two

short songs and a story. Every show had one central topic, like clouds, cows

or grass.

Then after five years of doing Just for Fun, word filtered down that the

university was going to get a television license.”

Once the license was granted, he and a quickly-assembled team were informed

they had about a year to develop a show suitable for broadcast. The campus

provided

them with a few old cameras and tripods. Headquarters was an abandoned science

building, which should have been condemned. Said Homme,“We literally

invented a studio as we went along. In the conversion process, we ripped

out the desks

in the biggest room in the place, the chemistry lab, trying to make the floor

as flat as possible. All that while, I was still doing the daily radio show.”

At that point he had no firm ideas on what manner of show to attempt for TV.

For the first few months he felt it wise to familiarize himself with the equipment

and learn how to operate it in a confined area. While he persistently drew

a blank, others around him were coming up with ideas for their own shows. “It

seemed everybody in radio was trying to get on television; they could see the

handwriting on the wall. Theatre and visual arts people, too, thought they had

ground floor opportunities. We in radio knew we were ‘in’ because

we already had valuable experience in daily commitment.”

That certainty was accompanied by an attitude many dedicated artists adopt

- pursuing art for art’s sake - as the university had stipulated that any

involvement with television would have to be conducted in spare time or after

hours with no pay. Recalled Homme, “We were all novices. Our director had

never directed, the production designer had never designed a set. And how would

you ever know what to pay whom? But we didn’t care. It was exciting

and we were allowed to experiment.”

In the meantime, in addition to his staff

position as music programmer at the university radio station, and extracurricular

television production activities,

he took on a part time job as a booth announcer in a small commercial station

(whose owner at one time worked at WHA radio) to help support his growing

family.

Homme kept drawing the blank until the day he was struck by “a sudden little

insight that there were no giants on TV.” His next thought was that perhaps

he could combine such a character with the “quiet” concept he liked.

The show’s name originated with his wife, Esther, when Homme expressed

the worry his character might be too frightening for young children. Her words

back to him: “Not if he were a friendly giant....”

Ideas then flew fast and furious. He thought about miniature sets to build, a

village to invent. The more he thought about the premise, the more he became

convinced it would work.

Developing abstractions into workable storylines and physical staging were

two enormous challenges to the small greenhorn ensemble. Serious experimentation

began late summer 1953, geared to meet a scheduled air-date of May 8, 1954.

Homme

defined an important element for the show. With children’s records highly

popular at the time, each show would feature a tune or two after which the giant

would recite a simple story. Ideal presentation, however, continued to elude

the group, and Homme’s confidence in the whole motif began to waver. “The

first set employed a sandbox and all manner of artefacts and characters needed

for a young audience to follow an unfolding plot,” he explained. “In

one tale, for example, there would be a little cow and a farmer in the sandbox,

and I’d mime the action with my hand while speaking. Somehow, it wasn’t

enough. Then we tried pipe cleaner puppets and constructed a miniature curtained

theatre. Nothing was working, and it came to the point where everyone wanted

to give up. Soon, people began telling me they thought that the giant himself

wasn’t enough, reasoning there were only so many times the camera could

pan up and down a tall guy telling a story. And then the workable scenario hit

me. Wouldn’t it make for better TV if the giant were to talk to someone

instead of just the camera all the time? And I realized the only logical character

a giant could speak eye-level with was a giraffe. I’d call him Jerome,

and he’d have to be six feet tall, my height.”

A rumour hung on that the station manager had been insistent on calling the

puppet Jeffrey and wanting it to speak with an English accent. If such a situation

had

existed, Homme would have been emphatically against making any changes, and

related that, “A variation on speech would have only served to confuse

young viewers who were only beginning to get a solid hang on speech habits.”

They next went to work on designing the actual puppet. Initial prototypes didn’t

function technically and were clumsy to operate. Some resembled camels and horses.

Homme contacted a student acquaintance from a nearby art school and gave him

specific instructions: “I don’t want anything funny about it,

no ping-pong ball eyes or the like. This giraffe is going to be funny by

what

he says and how he says it.”

A clay mould was sculpted by the student to serve as the form for a paper mâché head.

The plan included animating the lower jaw with a trigger-type mechanism. Then

things couldn’t get worse. As Homme described, “A flash flood deluged

the area, hitting the science building and our basement TV studio. The water

totally dissolved what I feel was the perfect model head. We’d even been

rehearsing friend and fellow employee, Ken Ohst, who was to have handled Jerome.

Now we were in real trouble. It was so close to going on the air and we knew

Jerome wasn’t going to be ready.”

The solution was found closer to home. Homme’s four-year-old son, Richard,

had a little polka-dot rooster hand puppet which he’d named Rusty. The

puppet was brought in for the next rehearsal, and as Homme related with a smile, “Ken

the giraffe-handler was informed the show would have to make a go with the

rooster. He indignantly declined, stating he preferred to wait for Jerome.

Luckily the

production designer, who liked to work with props, stepped in.”

The set was reworked to better accommodate the rooster. Originally the puppet

appeared in the same arched window as the giraffe. The only prop in the vicinity

of the window was a hanging bag with an elasticized top from which books and

other items were pulled. Then Homme felt it would seem natural for Rusty to

come and go through the bag, too. A hole was cut in the wall and the “Book Bag” attached

to it. Satisfied, he commented: “It worked like a charm, and we found

we could do all sorts of things. That bag became virtually bottomless. We

could get props onto the set - 50 feet of rope, a fish bowl, anything - without

awkwardness.

With that innovation, we knew we would have an interesting show with endless

possibilities.”

The first episode of The Friendly Giant aired on schedule, with Homme, the

rooster, and a last-minute addition, a Steiff cat puppet which would shake

its head agreeably

while Friendly read the story of the day. Within a few months, a number of

shows were picked up nationally by NET (now PBS). Not surprisingly, Homme wasn’t

sleeping well at the time, feeling he could only relax if he had plotted out

two week’s worth of shows. The question of audience reception was also

a concern. “We didn’t want another children’s production on

before us of after, because of the nature of our show. We still don’t,” said

Homme, maintaining that stance while alive.

Meanwhile, Jerome was still evolving. The sculptor managed to recreate the

mould and an almost-perfect paper mâché head from it. This time,

a test neck for the puppet crafted from cloth-covered aluminum rings gave

a too dragon-like

appearance. Once again, Homme found the answer at home. Esther proceeded

to create the first suitable neck for Jerome by using a ruddy-hued buckram-lined

beach

towel dabbed with blue spots (which filmed better in black and white than

would

have a lighter colour), which was then attached to the custom-made head.

Years later when the show began filming in colour in Canada, audiences readily

accepted

the oddly-coloured giraffe.

The last details about Jerome that Homme felt needed to be addressed were his

ears, as he had never liked the original ones. “Although very accurate

in design, they didn’t move or flop like real ones,” he stated. “They

were so stiff that if you clipped them on the window set you could really

hear it. So, I did some drastic surgery. Shortly before Jerome went on the

air for

the first time, I cut the ears right off with a hand saw. Then I took two

corks, wrapped window screening around them in a leaf form, and covered them

with

the same fabric as the neck. The insides of the ears we lined with grey velvet.

The

measure of movement was greatly improved.”

The day of Jerome’s premiere rehearsal brought a new chaos. Ohst, Jerome’s

handler who’d patiently awaited the day of the puppet’s return, was

ready and willing to go. But upon the new and improved giraffe’s arrival

at the studio, the set designer who’d been operating Rusty the Rooster

became highly distressed. Recalled Homme, “The guy was so ‘show-biz’ oriented

and just said point blank ‘I’m not going to be upstaged by that beast!’ Those

were the exact words he used.” (The set designer eventually ended up

with his own show called The Story Tree, produced in the same studio as The

Friendly

Giant.)

Homme’s production marched on sans the chanticleer, and its disappearance

was worked into the storylines. Keeping the memory alive with viewers, mention

of the puppet periodically came in asides, such as Friendly asking, “Where’s

Rusty today?” and Jerome answering, “Oh, he’s on his way to....” Before

long, however, when The Story Tree moved to a competing station, Ohst felt

comfortable about taking on the handling of both giraffe and rooster. Now

that the trio of

central characters was intact, the show achieved the congruity and atmosphere

Homme had strived for.

Much of the refreshing spontaneity came from never following a formal script.

Oftentimes the banter between giant and puppets was ad-lib. Homme revealed, “Shortly

before air time in the dressing room, we’d talk about the upcoming show,

and decide some things and dialogue exactly. Things like Jerome’s attitude

of the day. It was very similar to how we had planned segments for radio. But

we always left room to step outside our basic idea. Thankfully we also knew how

to rescue each other if a line, or even subject, was forgotten. If I got into

trouble, for example, Jerome might say, ‘You were telling me the other

day about....’ Whatever it was that had been forgotten, the prompt

was usually enough to jog the memory.”

Periodically a rescue involved more than one of the puppets delivering a reminder

line. Airing live the first few seasons sometimes demanded a strong sense of

humour and improvisational flair. Such skill and temperament came to the players’ aid

more than once, as during the course of one show themed on trees and leaves.

After the intro, Homme gave his customary giant’s whistle, expecting

Jerome to arrive with a hodgepodge of leaves in-maw. Rusty, instead, suddenly

appeared

at the mouth of the bag. Both puppets were being operated by Ken. The scene,

as Homme recalled, unfolded as follows:

Friendly: Where’s Jerome?

Rusty: I haven’t seen him.

Friendly: You don’t know where he is?

(Rusty is strangely quiet.)

Friendly: Well, I’ll whistle for him again.

Rusty: You do that....

(Homme whistles, and Jerome appears with his mouth full of colored

leaves.)

Friendly (taking leaves from Jerome’s mouth): These colours

are beautiful.

Jerome: Yes, they’re nice to look at.

Friendly (having no luck, turns now to the rooster): You know,

Rusty, we could press these leaves in a book, and I know just the

right book.

Rusty: (after a long pause) Which book would that be Friendly?

Friendly (firmly): A perfect book would be A Tree is Nice.

Rusty (again after a pause): It’s not down here, Friendly....

(Homme suddenly realizing he’d

forgotten to put the book into the book bag, skipped nary a beat

of dialogue to salvage the scene.)

Friendly: I know just where that book is. I was reading it

to the cats out by the East gate. You two stay right here, I’ll

be right back.

(“Then,” Homme recalled, “I backed off-camera, took off my

mike, quickly went out the door, down the hall, and up a flight of stairs, all

the while being as quiet as possible. I got the book, retraced my steps, struggled

to put the mike back on. All while the cameras were rolling and we were airing

live. The two cameramen were beside themselves trying to muffle their laughter.

Ken had ad-libbed to himself in two voices, saying the first things that popped

into his head, all the time I was gone. I stepped back onto the set and -” )

Friendly: I found it!

Rusty: No time to read it now, Friendly.

Friendly: I suppose we’ll read it tomorrow.

Jerome: I certainly hope so!

Friendly: So, what did you two talk about while I was gone?

Rusty & Jerome (emphatically, Ken’s one voice): Trees,

of course!

According to Homme, audience mail for the show indicated it was one of the best

they’d ever done, with no one the wiser the script hadn’t originally

played out that way. He was grateful that Ohst had “played it for all he

could”.

Between 1954 ad 1958 the same

team produced numerous programs intended for broadcast in public

schools. Special writing-themed shows didn’t teach children

the skill per se, but rather were intended to motivate them to that

end. “Above

all, we wanted to encourage young people to really think,” Homme

said. “The

subject of the day, for example, may have been an onomatopoeia, a

word like BANG! or CRASH! Then we’d give them an assignment

to come up with other words that sounded like what they meant. Or

we’d ask Rusty and Jerome to come

up with quiet or smooth words, which would inspire the children to

come up with words like ‘hush’. Even the shiest kids

loved to take part. These shows were aired on Wisconsin’s School

of the Air, some of which won four Ohio State Awards for Radio and

Television four years in a row."

|

| Homme

loved to reminisce about his long career with the CBC, and

compiled numerous scrapbooks full of memories, photos and

an exhaustive collection of articles about his long-running

TV show. |

In 1958 at the CBC’s invitation, Homme drove to Canada with Ohst and they

did their act live on a Sunday afternoon special. He hoped it would be his chance

to make his mark with a network he highly respected. “The CBC

was regarded as a Shangri-La to media educators in the business,

and it was

already a

big network then with wide open doors to those who could proficiently

produce educational

programming.”

Later back in Wisconsin, he was contacted by the CBC and offered

the opportunity to work at the network on a freelance basis. It was

an

offer Homme seriously

considered as by that time he was anxious to expand his horizons

professionally. He had already tried to market the show to major

U.S. networks without

success. None had a children’s department to speak of, and

while The Friendly Giant program was thought delightful, there was

reluctance

to broadcast a

show which

in their opinion would segment an audience. So, the choice was obvious.

He signed a 13-week contract with the CBC with another optioned 26

weeks if

all went well

in the ratings.

Things moved quickly. Solo, Homme drove to Toronto to join ACTRA

and make living arrangements for one year. Luck had it another CBC

employee

was

being transferred

for the same length of time to Montreal, making the search for short-term

housing brief. He returned to Wisconsin only long enough to sell

his house, pack family

and belongings in the station wagon, heading back to Toronto 10 days

after the youngest of his four children, Peter, was born. Temporary

lodging was

found at

a Kingston Road motel in Scarborough (a borough that was then more

farmland than suburb beachfront), arriving without their furniture

which had been

shipped separately

and would be stuck in Detroit for a week. They stopped by the empty

house everyday in Don Mills, near E.P. Taylor’s and other farms, to enjoy a kitchenette

suite and hotplate bought in the pinch.(A permanent home was found in the same

vicinity after the CBC option was picked up, and the family wasn’t at all

disturbed by, as Homme put it, “Waking up in the morning to cows mooing.”)

With the personal front in order, Homme’s only worry was the show. The

biggest setback was coming to Canada knowing his puppeteer had decided to remain

in Wisconsin, but luck stepped in again when he happened across the CBC radio

program Out of this World, written and performed by Rod Coneybeare in multiple

roles. As Homme extolled the discovery, “Rod was a gift from

Heaven. He could act, had imagination, and could play more than one

part. He

was ideal for

our needs.”

Coneybeare at first was reluctant to try on either puppet, but a

surprising change occurred when he was screen-tested in the studio.

According

to Homme, Coneybeare

dramatically “came to life, like a lot of kids will when you give them

a make-believe role. He was perfect with the voices of Rusty and Jerome. Without

any rehearsal we fell into an ad-lib act like we’d been doing

it together all our lives.”

Costuming was one element the CBC took upon itself to oversee. Esther

had designed the giant’s original costume in denim. The network budgeted for suits to

be made of costly raw silk imported from India. (At the time of Homme’s

death several of the fine tunics were still hanging in his closet.) The giant’s

original boots in Wisconsin had been borrowed from a theatre actor who used them

to play Santa Claus at Christmas; at the CBC, Friendly’s were

manufactured by the same company which made all the boots for the

Stratford theatre

company.

The bigger CBC budget enabled Homme to hire “real musicians” for

the show’s staged concerts. The repertoire included everything from 15th

century ballads, to folk, Rodgers & Hart, and even a little jazz. Periodically

the talents of puppet designers John and Linda Keogh, both now deceased, were

utilized. Leading Canadian puppeteers once featured at Expo ‘67,

after a move to Mexico their place was taken from the late 1960s

through 1985 by

their daughter Nina, who also became responsible for hiring other

musical puppet talent

for the show.

The ratio of book to music shows was about four to one, with music

episodes being more expensive to produce. Homme believed the format’s popular success

came from limiting each 15-minute program to one subject, book or music, with

gentle presentation. He reasoned that, “Early TV like Howdy-Doody was literally

shouting at kids. The standard formula was ‘hit kids over the head, be

loud, be funny’. Going totally against that approach, I wanted to speak

kindly and intelligently, as though to my own son. I would never speak down to

a young audience. I think it was the best way to convey the ‘considerateness’ we

wanted to encourage - to show how to be good through being thoughtful.”

Homme consequently ensured that the good-natured humour of the show

contained nothing that would puzzle or irritate a child. The fun,

however, was

always educated enough to appeal to adults who’d often be watching with their children.

As he said, “I kind of regarded it as working both sides of

the street.”

Numerous goals had been set as to how the show would reach and affect

children academically. High on the list was to introduce children

to words and music

they weren’t likely to encounter elsewhere. Striving to inventively convey the

meanings of things and often difficult concepts, Homme knew he was always taking

the chance of going over his young audience’s head. Another important objective

was to attempt to increase attention span, one reason for limiting shows to a

single main subject. Elaborated Homme, “You have to go back

to a sense of Greek form and style. The whole thing has to be all

of a piece.

It may

have variety, but it must have unity. The trick is to get it exact.

Some who try

to achieve it destroy the unity by their choice of variety.”

He also felt it unnecessary to

research his audience to determine what would and wouldn’t

work on the show. His only guideline was that he had to meet children

on their intellectual level. He knew, for example, that a young child

didn’t have any grasp at all of historic time, reasoning that, “Three

hundred years ago is like last Tuesday to them. So you have fun with

it, like in this conversation with Jerome, which a child could easily

understand:

Jerome: Friendly, do you think they had

peanut butter 300 years ago?

Friendly: Probably not.

Jerome, Well, you know, back then, if you had a hammer and a peanut,

you could make a little peanut butter....”

That appealing format made the show an instant

hit when it began airing September 1958. It ran on CBC 28 years, signing

off with a last original show in March

1985. Since then, it frequently reruns somewhere in Canada on cable or

satellite.

For a number of years after retiring Homme did the high school circuit,

and was an annual featured - albeit unexpected - visitor to Ryerson

Polytechnic Institute

(RPI). He never felt a stranger among an audience comprised mainly

of kids who’d

grown up watching him on TV. Without costume, he’d be dressed in a business

suit, shirt, and tie, and have his hair combed back. The recorder would be hidden

in an inner overcoat pocket. He remembered , “The RPI instructor would

announce ‘I’d like to introduce a gentleman who’s been on television

for 35 years, and he’ll be speaking on the subject closest to him’.

I’d get up quietly and smile. Then I’d turn my back on the

room, take my glasses off, pull my hair down, take out the recorder and

begin to

play Early One Morning. There would be instant recognition and surprise.”

|

| Robert

and Esther Homme were happy in their rural Grafton, Ontario

home following his retiring from the CBC. They were always

welcoming friends and family in the comfortable country setting.

In the winter, it wasn’t unusual to see Esther pick

up a shovel and clear snow off a large deck, or have Robert

ask you to wait a moment while he put another log into the

basement woodburning stove which helped heat their home. |

The Hommes became permanent residents of Grafton, Ontario in 1986,

first becoming aware of the area in 1958 on drives east from Toronto.

During

numerous trips

to Expo ‘67 they had noticed highway exit signs like “Shelter

Valley Road”, and feeling drawn by the pleasant names, their

curiosity grew enough to investigate the area’s rolling hills

further.

“We drove north up one of the exits. In many ways the landscape was similar

to rural Wisconsin where I grew up,” said Homme. In 1969 an

initial 50 secluded acres was purchased, thick with fir trees, gullies,

and ribboned with

a meandering trout stream. They added to the acreage over the years.

By 1970 construction was completed on a cedar log cabin, set atop

a steep knoll, well

in from the road. It was perfect for a giant’s weekend hideaway,

and became the family’s vacation retreat when The Friendly

Giant was on hiatus during the summer months. Over the years the

home sprawled

into two stories

and a

separate coach house was built.

The picturesque property, wildlife, and back porch clustered with

bird feeders may have provided a peaceful backdrop to retirement,

but Homme

was never

content to sit back in the easy chair and count hummingbirds. (He

and Esther, however,

spent many a quiet evening together watching their favourite TV show,

Murder, She Wrote.) Even while combating advanced terminal prostate

cancer, and

experiencing increasing difficulty walking, he was still a busy man.

Never abandoning

the clarinet, he and neighbour accomplished pianist Shelagh Purcell

occasionally headlined at popular local venues such as the Oasis

Bar & Grill in Cobourg

and the Grafton Village Inn. (In a special local1998 ceremony because of his

illness, then Governor-General Romeo LeBlanc, whose office stated Homme was “an

icon of childhood”, invested him as a Member of the Order of Canada at

the rural inn.) He often marvelled at Purcell’s talent, in that “She

can play any song ever written, in any key on the piano. We met at

a party and began to play together almost by accident. One of our

favourite

songs

is Why

Do I Love You?

|

| Homme

often relaxed in his favourite chair in the den, from where

he could enjoy a view of his property, or speak with Esther

from almost any room on the main floor. In his hand was a

picture taken of him in attendance at the ceremony honouring

him as a Member of the Order of Canada in 1998. Not many

months later after this recognition of his talent and service

to Canada, Homme succumbed to the illness he had fought so

bravely. |

Homme, also of Norwegian ancestry, proudly became a Canadian citizen in the early

1990s, while retaining his American citizenship. He continued to personally answer

fan mail, even during the lowest points of his progressing illness. Two years

after his death on May 3, 2000, wife Esther continued to manage their home and

property herself, even while slowly recovering from a broken rib and walking

with a cane. She still hikes trails through the woods she and Homme once walked

together. Mail for Friendly still trickles in. And friends drop by, to make sure

the long driveway’s ploughed out if it’s winter, or with an article

in hand that’s made mention of her husband. She carefully oversees

all broadcast and other rights related to The Friendly Giant show

and image. Above

all, their four children and assorted grandchildren are the greatest

reminder to Esther of a five decade-plus marriage filled with non-stop

adventure and

intellectual gaiety.

Throughout the years, the couple was often seen frequenting any one of many favourite

dining spots near their home. Whenever Homme was recognized, he just gave his

quiet smile, and perhaps signed an autograph. After all, as his character would

likely have said, wouldn’t that have been the considerate thing

for a friendly giant to do? Copyright © 1998: L. Chrystal Dmitrovic

Copyright © June 2002: L. Chrystal Dmitrovic

Copyright © October 2003: L. Chrystal Dmitrovic

|