The Empress Interview:

In discussion with William Perry about his Music for Silent Film, Film and Television, and the Stage

Conductor Paul Phillips, soprano Helen Kearns and composer William Perry together in Dublin in 2011 during recording sessions for Music for Great Films of the Silent Era CD (Part One)

LC: Are there any other songs/film scores that you would have liked to include on the first Silent Film CD? If so, which ones and why?

Home Page |

Newsletter, |

William Perry: When preparing the first orchestral CD I already had in mind a second CD and possibly a third. A number of my favorite scores have not yet been given full orchestral treatment, though that is an on-going project. In the works just now is the swashbuckling music for Douglas Fairbanks Sr in The Iron Mask (1929), following which will probably be Fairbanks again in The Mark of Zorro (1920). One of my favorite films of all time is The General (1926) with Buster Keaton, and many people have asked for an orchestral version of that. I will be happy to comply as soon as time permits.

LC: Why did you choose the 3 particular silent film Rhapsodies for the CD? Is it because of the timeless appeal of those films? And what in your score compositions for these especially stand out for you?

William Perry: In choosing the films for The Silent Years rhapsodies, I wanted to include three different historical periods in three different countries so I could answer the musical challenges this would present. And I wanted each film to have a name-above-title actor of the Silent Era in an iconic performance. I should also say, perhaps more humbly, that I have had some success over the years writing love music and creating lush love themes. These three films had scenes and relationships that cried out for music of this genre.

LC: Do you have a personal favourite among your film scores, either from this CD or another, and why?

William Perry: I have too many favorites to mention here, but one film that has never failed to move and inspire me is King Vidor’s masterpiece, The Crowd, from 1928. I had a chance to perform this film with Mr. Vidor in attendance, and we talked at some length about how beautifully the scenes were edited so that my musical phrases would just naturally fall into place. He then let me in on a small secret . . he edited the film using Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony as his guide.

LC: How did you become inspired to write the Mark Twain stage musical? It seemed to be a truly natural follow-up to the PBS TV series.

William Perry: Yes, the PBS Mark Twain Series came first, and it ran from 1980 to 1986. As a result of its success, the production company I had formed with my co-producer, Jane Iredale, (Great Amwell) was commissioned to fashion a biographical Mark Twain stage musical. That opened in 1987 and ran every summer until 1995.

LC: How did Lillian Gish become involved with your four-hour Huckleberry Finn movie of the series?

William Perry: Lillian had been the host of the second series of The Silent Years and a treasured acquaintance. She was pleased to play a role in our adaptation of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and came to Kentucky for the location shooting.

LC: You have composed music and scores before, during and after seeing film or live visuals. Do you prefer any particular order when composing, either without seeing the film first, or viewing the film before composing the music? Does either way offer similar opportunities when writing scores or individual songs?

William Perry: Although I improvised many silent film scores at sight when I was performing regularly at the Museum of Modern art, I always preferred to screen each film first when time and scheduled permitted. When I was preparing to record a score for posterity, I would study the film a number of times, taking notes and carefully composing the music for each scene.

LC: What have been some of the greatest challenges you've faced when composing and/or producing for the stage, for television, or for film silent or talkie? In the same vein, what do you feel have been your greatest accomplishments? What works are you are completely satisfied with in terms of "saying with music" exactly what you wanted to?

William Perry: As any good parent would say, I love all my “children” and try not to show favoritism. But somewhat arbitrarily, I might suggest a special affection for my silent film scores for The Gold Rush, The General, The Beloved Rogue, Orphans of the Storm, and The Crowd. I also have great fondness for the TV film scores to Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Patrick Day, Lillian Gish and William Perry on an exterior location set of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, broadcast on American Playhouse in 1986. (Photo: John Seakwood)

LC: You wrote so many silent film scores while with MOMA, with many of the films subsequently released on VHS/laser disc and DVD. Was the time with MOMA an exceptionally highly charged creative period for you, which overlapped into composing music and producing television for PBS?

William Perry: Highly charged, yes. Highly satisfying, yes plus.

LC: From all appearances it would seem that music was forming within and emanating from you 24 hours a day. It must have been exciting; were the pace and expectations ever exhausting regarding the creative musical demands that you were meeting and perhaps exceeding?

William Perry: I don’t believe fatigue was ever allowed to interrupt my schedule. And that’s still true today. I might pause from time to time for a single malt Scotch, but for fatigue or exhaustion, no.

LC: Do you have a special approach to the actual composing of a score or piece of music; different approaches for different entities?

William Perry: Composing for concert performance is a somewhat lonely occupation, but composing a film score is highly collaborative. I was fortunate when working on the Mark Twain Series that I was the producer as well as composer. I was on the set every day and actually could confer with the director about what kind of music would set the mood or bridge the scenes we were shooting.

LC: Do you ever get caught up in a flow or surge when composing and later find many hours have passed? Might an idea, a few bars of a theme running in your mind, emerge immediately, or are these worked on in the subconscious for any amount of time and can abound into formal bars of music when the inner formulation is ready and brimming? Or in combination of that?

William Perry: Inspiration can show up almost any time, though I have yet to see anyone scratching out melodic ideas on a restaurant napkin as legend would have us believe. I think inspiration comes from concentration, and early on I learned about Mark Twain’s habit of leaving for his study after breakfast and not reappearing until the end of the day, ready to read to his family what he had just written. That set a good example for me, although I didn’t copy his habit of taking twelve cigars along.

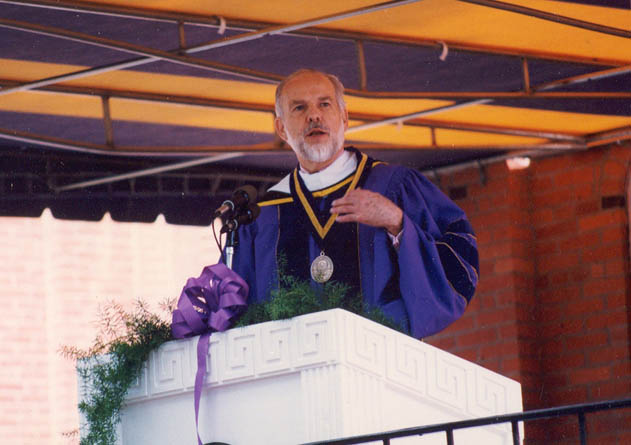

William Perry during his commencement address after being awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters (Litt D) by Elmira College, in recognition of his contributions to the field of Mark Twain studies. Elmira College in upstate New York is a center of Mark Twain academic study. Twain's famous outdoor study is now located on the campus, and the College owns and offers graduate studies in the summer home where he wrote many of his best-known books.

Says Perry, "Mark Twain is buried in Elmira, and I was born about a half-mile from his gravesite. My grandmother used to watch him walk the streets in his white suit, and I came to know his niece. Not surprisingly, this close connection with the author is what led me to devote a number of years to producing films and stage versions of his works."

LC: Creativity in any field knows no limits, and one musical revelation while composing can often spur a next, and then a next one. It's fascinating that you can pick up a piece you composed years previously, and rework it into a new score that was always meant to be. In that light, when do you realize that a score is truly complete? (And at times there have been years between you originally composing a piece of music/score and then evolving it for later purposes.)

William Perry: We have a saying in film editing that a scene, or for that matter an entire film, is never completed, but simply abandoned when the search for perfection is no longer producing positive results. I like having deadlines . . .a film release date or a concert premiere date. It channels one’s energy into doing often remarkable work that oceans of extra time would probably not improve upon.

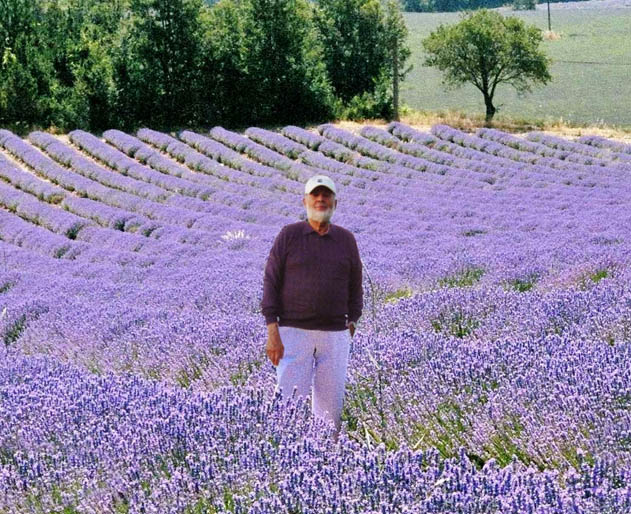

LC: You have often travelled abroad for assignments and projects, as such with your recent working trip to the Provence region of France. Did the beauty of the area inspire compositions for your latest CD project titled Toujours Provence?

William Perry: These photos reflect my inspirational background work for Toujours Provence, and are quite colorful. The second movement of the upcoming Toujours Provence orchestral suite celebrates the fields of lavender (top) photo for which Provence is famous. The third movement is a depiction of Van Gogh’s famous "Café Terrace at Night" painting. The café (bottom), which is in Arles, pretty much exists as it did in Van Gogh’s day.

William Perry: Absolutely. The beauty, the history, the artistic culture, the colorful spirit of the people. It’s a unique part of the world. Toujours Provence will be a four movement orchestral suite with a featured solo piano. It is at least a year away from completion because I am devoting my current time to revising the Mark Twain Musical (Mr. Mark Twain) to make it suitable for smaller stages. The original production called for a cast of 60 and had a horse and carriage, a floating raft and a 55 foot high Mississippi riverboat.

LC: When day's work is done, and you have your feet up relaxing, what music compositions by others or ensembles/orchestras might you enjoy listening to?

William Perry: Somehow I don’t recall putting my feet up and relaxing, but if I were to, I would probably be listening to Beethoven's Late string quartets, or to some favorite orchestral pieces from the English pastoral school by composers such as Delius, Vaughan Williams, and Holst.

WILLIAM PERRY - MUSICAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Over the years I have worked with some wonderful teachers and colleagues. Many of them have passed on. But still among us, happily, are: Donald Sosin, Peter Breiner, Yehuda Hanani, Michael Chertock, Ambra Albek, William David Brohn, Timothy Hutchins, Jack Waddell, Wallis Giunta, Nick Byrne, John Brancy, William Eddins, Ben Model, Malcolm Rudland and so many others.

And if I may, I would like to give a special vote of appreciation to three comrades who in recent years have been instrumental (sorry!) in making my musical life so special:

Paul Phillips: a musical polymath (conductor, composer, educator, author, musicologist), whose extraordinary understanding of music in all its forms and whose ability to communicate it perfectly to orchestra and audience, is a composer’s dream.

Paul Phillips on the podium. Says Perry, "Paul has the finest baton technique of any conductor I know."

Robert Nowak: a master of orchestration and arranging and equally remarkable, the finest music engraver in the business. I can’t imagine a musical world without him.

William Perry and Robert Nowak consulting on a score at the Dublin recording of Music from Great Films of the Silent Era – Part 2 in 2014

Tim Handley: a record producer and engineer of exquisite skill and taste, whose Grammy Award for best classical producer in the world is more than deserved.

Grammy Award-winning Producer and Sound Engineer Tim Handley at his console at the National Concert Hall, Dublin