Reviews: William Perry’s Jamestown Concerto

and The Innocents Abroad CDs

Before listening to the music, it was a joy to read the biographical liner notes to William Perry's Jamestown Concerto CD. Apart from carrying a wealth of background information, the notes were a view back, revealing fascinating details about the composer's experiences at his earliest career stages.

Home Page |

Newsletter, |

Although not directly related to the CD being reviewed, mention is made of Perry while at Harvard University for music studies and his occasion as a conductor when he organized a student orchestra and chorus. In a performance of Handel's Royal Fireworks Music, it was described that he provided a wind section that featured 12 oboes, and 8 bassoons (which would have supplied weight and might to any royal refrain) and, a “serpent.”

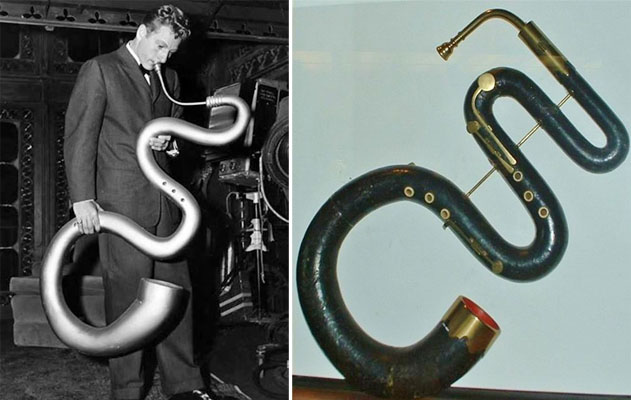

What exactly is this “serpent” and what does it sound like? This “horn” or a similar instrument was “played” by Danny Kaye, for example, in A Song is Born (1948). I asked Mr. Perry if he had employed it as an instrument in any of his own compositions since that performance, and he replied “I have never used a Serpent in any of my [recorded] stuff, but, as you know, I did compose for the instrument that succeeded it, that being the Ophicleide. The Serpent is not easy to play and at times can present problems in maintaining pitch. Handel said “It not be the serpent that seduced Eve?” And the great film composer, David Raksin, said that “the Serpent sounds like a donkey with emotional problems.”

Danny Kaye (left) performing with a samba horn in a publicity photo from A Song is Born (1948), and a photo (right) courtesy of William Perry depicting a real "serpent" horn

About the photo he provided, Perry notes “I understand that Bernard Herrmann used a serpent in the scores of White Witch Doctor (1953) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), as did Jerry Goldsmith in his score for Alien (1979). I never found a place for it in any of my film scores. The Danny Kaye instrument is similar but looks like it was created in the prop shop.”

I now nod in understanding about the Serpent. And, after many decades, I think I've finally discovered, thanks to Perry mentioning it in connection to the film, what instrument was heard when the “giant dinosaur” iguanas cavorted menacingly onscreen in Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959).

Perry has often included a broad variety and largess of group of instruments in his orchestras. Regarding the university performance of Handel, he states, “It may be of interest to know that Handel’s original orchestra for “The Royal Fireworks” included 24 oboes, 12 bassoons and a contrabassoon, 9 natural trumpets, 9 natural horns, 3 pairs of kettle drums and side drums. No strings … the King loved brass and woodwinds. I guess you can collect 24 oboes and 12 bassoons by Royal command. I felt pleased that 12 oboists and 8 bassoonists voluntarily came from all around New England for our performance. The Boston Symphony supplied the contrabassoonist.”

Not in the liner notes, and equally enlightening, is a revealed fondness and respect for his own instruments, which may have their own delightful histories. Perry confides, for example, “My harpsichord was built in Germany by Martin Sassmann, probably in the late 1960s. Building harpsichords seems like such a peaceful pursuit, but in the Second World War, Sassmann was a Messerschmitt fighter pilot.”

That brings to mind the spontaneous Silent Night duet sung between opposing battle troops in WWI during a brief "ceasefire." Music can truly transcend war and be a harbinger for peace.

And now, from serpents on to reviews proper ….

William Perry's Jamestown Concerto features Yehuda Hanani as cello soloist, accompanied by the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra conducted by William Eddins. Hanani's cello serves as "lead vocal," a distinct voice acting as "narrator" in this musical historical tale.

The NAXOS world premiere recording is representative of the concept of using music as a medium to share histories of people, places or events in continuity through time. The musical staff "read out note by note" is comparatively a walking staff that Hebrew fathers "scored" to pass along their oral history. For centuries they recited from memory, "reading and singing" according to the etched marks on the the staff. The practice was effective until formal writing was invented and came into common use.

Akin to the chicken or the egg dilemma, man likely had music before literature, with melody and narrative used to "record" milestones in history, myth, legend, and lore. In our modern era with all the literary options and amenities available, music apart from being entertainment, is still a mode to enrich tribute to historic, notable moments of people and cultures. It's an artistic tool, capably capsuling our times and places as in familiar informal ditties and illuminating odes, within a plethora of song styles and formats. Patriotic national anthems, prose set to music representative of a country's glory and pride, also fall under this category.

Perry composed the Jamestown Concerto to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in Virginia, the first permanent colony established in what would one day be known as The United States of America. The concerto had its public performance and later radio broadcast premieres in 2007, with the US National Public Radio broadcast occurring on the historic commemoration date of May 13, 2007 - the very day colonists landed in Virginia.

As for using visuals to research the Jamestown settlement in preparation to compose his concerto, or studying old paintings or watching movies for inspiration and historical background, Perry explains that, “I studied 17th century history and literature at college and had given concerts of early 17th century music.”

Composer William Perry in his famous Stravinsky pose

I - London 1606. The Virginia Company

In this first movement, the cello lyrically introduces the concerto in the Old World as though far off in the distance, then the music "parts" a cloud cover over London landmarks and its winding river like an inquisitive motion picture camera. Finally, it settles focus on a bustling throng in a crowded square. It's "follow me" invitation eases into forward-looking visions and introduces suitcases full of dreams for a better life. The melody rests upon families seeking freedom in a new homeland, businesses dreaming for lucre and gain in uncharted territory. This preamble music prepares for the expedition and the journey from high-finance London to presumed riches in that mysterious land across the sea. It's all a go, come what may. It's already a "no turning back" mindset in the planning stages, with the melody organized "in its thinking" and performance. The cello has introduced and set the stage for its continuing narrative in the concerto.

It was John Milton (father of the poet) whose "germ of a melody" as quoted in the CD liner notes that stood out and impressed Perry to expand on it for the first movement of the concerto. For this review, Perry explains, "It was a rich melody, and the verse celebrated Fair Oriana, which is to say, Queen Elizabeth."

The movement overall speaks with gentle suspense in the midst of preparations for the journey of discovery. An exhilaration then sets in as the sensation of expectation

billows out sails of greats ships as they forge across the expanse of sea. Many sunsets and sunrises will turn with the Earth before the new horizon is seen. The horns, specifically French horns, are exceptionally radiant and rich, leading the colonists to finally reach the New Land in 1607.

II - Settlements Along the River

This second movement is so evocative of all that discovery is and the elation it can stir. The music takes first cautious steps in a new land, and with no ready-made roads perhaps follows a game trail or a native footpath that can be barely seen in the scrub. The river has a gentle flow, with misty clouds of flying insects hovering above the water. Instrumentally, the orchestra drifts you along through rapids, then through the fading light of afternoon. Settlers wave to other rafters, watching fishing lines catch a glisten of water as they are lowered and raised. Then a military march marks an abrupt change as troops organize their journey and meet skirmishes with the new land's inhabitants - as well as greeting other friendly tribes who will eventually become the settlements' means of surviving the first terrible winters.

Perry employs single or groups of instruments to represent various people and situations. When first settling into the wilds along the James River, territory reigned over by Chief Powhatan, the chief is given lordly voice by a single trombone - with an echo supplied by another solo horn. When Captain John Smith appears to subdue the fighting between settlers and native tribes, his strength and authority is suggested by triading (and likely a little tirading) of trumpets. The tween Indian princess Pocahontas is brought into vision by a solo flute against a solo cello pizzicato.

III - The Long Winters

Kettle drums open the third movement, and the cello solo is reverently romantic. The pizzicato in a combo of instruments inspires a stunning visual. Like seen through a shimmery halo, the first snow of the season is falling, lightly dusting the forest and cabin rooftops. Large billowy flakes play tag in the wind currents as the river freezes over slowly; soon the landscape becomes a few trickles of water flowing in cracks or puddling on stretches of ice. With the clinging cold and the building blankets of deep snow, the future seems bleak. Still, with spirit and hope, settlers and villagers go out into the cold of day to hunt, to visit, and to trade with natives and other settlers along the river.

Overt weepy strings drip sentimental tears for a few bars, suggesting that the Old World - its safety, its security, its known challenges, its everyday problems diminished in view of the greater unknowns of the New World - is missed dearly. Perry describes an especially poignant section of bars - a slow, wavy gliding technique directed for the strings at 1:27 to 1:39 in movement III, The Long Winters - as, "In that passage the cello soloist and the principal cello in the orchestra are playing string harmonics at intervals of a fourth."

In a pensive spell, the settlement still not "home," the melody reflects the worries of the new-landers, whether or not theirs had been a right decision to settle in an unknown land. Still, hope glimmers for provision, for survival, a drawing together of the settlement for strength, warmth and renewed expectation. The cello solo is now a gently comforting, inspiring voice, and the colonists are longing for home, reflected by the quite haunting passage where the solo cello duets with an oboe d’amore.

Come Spring, the cello voice gains energy and breaks into happier harmonies tremulous with sprite joy and even a twinkle of frivolity. The kettle drums briefly announce Winter's end. Overtones in the cascading strings assuredly indicate that Spring and new hope is returning. To have made it through the bleak dark of Winter is reason to celebrate. The settlements, despite casualties, had survived, and settlers could begin living the next chapter, thankful and looking forward to fulfilling those suitcase dreams carried with them to their new land.

IV - Pocahontas in London

With this fourth movement, Perry chose to incorporate a fragment of extant music of the period as an aria for the cello. This little historical nugget was originally part of "The Vision of Delight" staged at a masque held at Whitehall Palace, which Pocahontas attended in 1616.

Previous to this interlude in Perry's composition, the orchestra climbed a musical hill, suggestive of the Indian Princess' arrival and the procession to see the Queen. Included was a "gigue," a lively baroque dance musically inspired by the British jig. Amazing chording and the orchestra's expressive emotional longing highlights this passage. Sliding fingers languidly connect to create notes; melody elevates to sunbeams breaking through wish-holding clouds. A trombone solos moodily as all the orchestra instruments seem to be conversing with each other with great interest, rather than the occasion being a gathering of musicians following a score. A slowing horn phrase then becomes an abrupt pause, with a forte pizzicato stop-note from the string basses and cellos emphasizing a plea from Powhattan for Pocahontas to return home. Sadly - and this is reflected in the melody - Pocahontas, about to return home, had already given up her spirit as the ship departed the English harbour. The orchestra ebbs toward closure. And what was that instrument gently striking single melody notes behind the last bars of the cello in the last 16 seconds of the movement, so reverently played? "A harp in triple octaves," Perry reveals.

V - Jamestown Four Hundred Years On

Drifting forward year by year, drifting toward the future in this last movement of Perry's concerto, it took numerous decades for the colony to establish itself successfully.

And suddenly, it is four hundred years later - the first colony had really "arrived." Having survived its most difficult early years, the 5th movement is a confident, victorious finale; with echos of the earlier movements, it has the happy emphasis of a colony that has now stood for centuries as a testament to perseverance. It melodically reminisces with the first movement, but is now more vigorous and shifts into supplementary melody notes. The orchestra flourishes in percussion, and a brilliantly vigorous cello vocal atop horns is exultantly accompanied by ecstatic cymbal clashes. The orchestra hails as a proudly marching processional, celebrating the little colony that beat the odds. The once frail sapling Jamestown endured, and to this day is remembered as the flagship of all colonial triumphs.

The dawn of America's rich history, its first people and formative years, are so wonderfully preserved musically for the record by William Perry in his Jamestown Concerto. The interpretation through the score gives the listener the chance to easily imagine all about the beginnings of a country - all that was sublime, its worst challenges, and the hard fought-for triumphs of its first settlers. From a colony, to a country to be for always ….

Please note: While this review has been dedicated to Perry’s Jamestown Concerto, buyers and listeners of the CD will be pleased to know that Yehuda Hanani includes two other remarkable performances of American Music for Cello and Orchestra: William Schuman’s A Song of Orpheus, introduced by actress Jane Alexander, and Virgil Thomson’s colorful Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra.

Composer William Perry has had a long multi-generational relationship with Mark Twain, so to speak. The author was a familiar sight to his grandmother; and Perry came to know his niece. Explains Perry, "Mark Twain spent his summers at Quarry Farm, on a hill overlooking my native city of Elmira, NY. When he came down into town, as my grandmother pointed out, he was probably heading for Klapproth’s Tavern, his favorite watering-hole. Some portions of the original tavern are built into the Library at Elmira College. Mark Twain’s niece, Ida Langdon, was Chairman of the English Department at Elmira College for many years. She was a good friend of my family."

This intertwining of lives virtually made it inevitable that Perry would one day evolve the connections into artistic substance. It was more fate than required reading in a school setting that would lead to Perry producing and composing for a major Twain-inspired series of films. Says Perry matter of factly,“"I have been associated one way or other with Mark Twain all my life. It was quite natural that I would one day develop a series of films based on his books.”

Perry, however, might not have foreseen that his Mark Twain films would one day win the most coveted recognition in the broadcasting industry, the Peabody Award.

The six films in the Mark Twain series, co-produced by William Perry’s own Great Amwell Company and the Nebraska Educational Network and other international production companies, premiered on PBS in the USA and experienced hugely popular screenings worldwide. (The films were seen simultaneously in Canada, with the American network a part of cable packages or picked up by analog antenna.) According to the CD liner notes, all the films “were originally sponsored and premiered by the national television networks of the United States (PBS) [as mentioned], Germany, Austria, Italy and France and have since been seen throughout the world.”

The Twain films are musically rife and ripe with international flavour and atmosphere, with Perry’s scores, and background/incidental passage for individual scenes, complementing well the visuals and the issues which at times were controversial. The range and descriptive prowess of Twain in his storylines always ultimately involves the reader emotionally – and Perry has matched the author’s particular creativity with movements that authenticate and define those folk tales with a true sense of what it like was to live in those long-gone days.

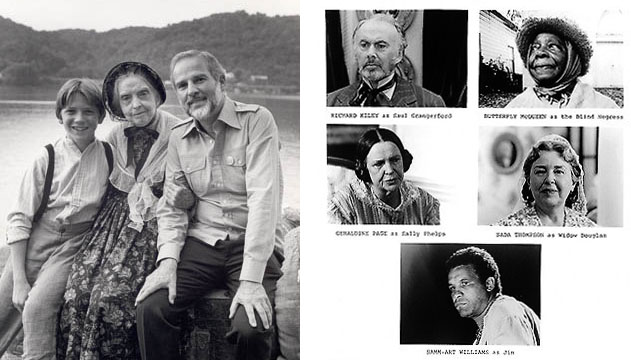

For the four-hour adaptation of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Perry was re-acquainted with Lillian Gish, with whom he'd worked during production of the second Silent Film Years series in 1975, when she was engaged as the host. Onset, he was photographed with Gish, Patrick Day, Butterfly McQueen (Prissy from Gone With The Wind). Other distinguished players, such as actress Geraldine Page and actors Frederic Forrest and Richard Kiley were among the all-star cast. For Perry, it was all quite functional. “I was on the set every day in both roles as producer and composer,” he says simply.

Left: Patrick Day, Lillian Gish and William Perry on an exterior location set of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, broadcast on American Playhouse in 1986. (Photo: John Seakwood)

Right: Other players in the 4-hour film: Richard Kiley, Butterfly McQueen, Geraldine Page, Sada Thompson, and Samm-Art Williams

The world is much more “politically correct” these days. As to there being anything Perry might have have approached differently if he were to produce the films today, one wonders if he would remain faithful to the time of Twain and the context of his original works. Perry took a firm stand during the production of the series, saying, “One of our sponsors withdrew because of our use of the “N” word in Pudd’nhead Wilson. We had no problem finding a different sponsor. We insisted on being true to Twain and his period.”

All the films had illustrious casts. Robert Lansing and Marcy Walker appeared in Life on the Mississippi. Brooke Adams, David Ogden Stiers and Barry Morse featured in The Innocents Abroad. Pat Hingle and Cynthia Nixon appeared in The Private History of a Campaign That Failed. Perry recalls, “Virtually every actor we approached felt excited about the association with a Mark Twain classic book. And the parts I could offer were rich and interesting.”

In The Film section CD liner notes, written by Perry's associate producer of the films, Jane Iredale, it's stated that a scene deleted in the Huck Finn book was restored for Life on the Mississippi, and refers to the music track, The Raftsmen. It has been documented by historian Dr. Allan Gribben that Twain originally heeded his publisher’s opinion to omit the passage. Perry's film marks the first time that the raftsmen passage was restored not only in storyline form for the screen, but given a musical treatment as well.

Dr. Gribben also described about the passage, as published in the American edition of Life on the Mississippi: “This episode, with its strutting, pugnacious braggarts and its chilling ghost tale about a child’s murder, contains some of Mark Twain’s best writing. Its restoration here [in the book] enables readers to savor more of Twain’s contributions to the then-reigning “Local Color” school of fiction that prized vivid descriptions of an area’s vocations and peculiarities.”

Perry concurred, stating, “We decided that the scene was so colorful and so exciting that we would use it in our adaptation.”

While working on location in Vienna for The Mysterious Stranger, composer-producer-fundraiser Perry also stepped in as conductor. He was required to replace the original conductor at a moment's notice, and had to conduct with an improvised conductor's baton.

Perry explained in “The Vienna Connection to The Mark Twain Series of Film” in the November 2016 issue of The Empress Arts & Music Zine, “Legendary Composer William Perry – Creating the Score, Silent to Sound”:

“Interesting sidelight. This was the third of the Mark Twain films, and my scores for the previous two had been recorded by the Saint Louis Symphony conducted by Leonard Slatkin. He was due to conduct this third score in Vienna, but missed his plane in New York. The members of the Vienna Symphony staff came to me with small freshly cut branches from the Vienna woods since I would now be doing the conducting and would need a baton! I continued as conductor for the remainder of the series.”

He adds now (with a smile), “The Vienna Symphony is so great that I could have conducted with a soup ladle.”

The cast again, was remarkable, and included Chris Makepeace, Christoph Waltz, Fred Gwynne and Lance Kerwin. The Mysterious Stranger’s original storyline has been much debated as to what true or final form can be attributed to Twain. The choice for the tale's approach being a “dream within a dream within a dream” is fantastical. Regarding that process, Perry says, “We brought together four of the country’s leading Twain scholars, and they helped us decide which version of The Mysterious Stranger to use.”

This series of films certainly depicted the amazing life and times and imagination of Mark Twain, as does Perry’s music give flesh and bones to the emotion, adventure, drama and humour of the stories. As for any other Mark Twain tale that he would have produced and for which he would have composed the score? Perry confides, “I always wanted to dramatize Roughing It, and had the funds been available, we would have done it. A great chance to write a Western score. We can’t outsource all those cowboy assignments to Morricone!”

From the CD liner notes, The Innocents Abroad and other Mark Twain films, excerpt from The Music written by Jane Iredale:

“For all of these, Perry has created music completely appropriate to the subject matter, with a common thread of melodic sweep combined with wit and inventiveness. His use of wordless chorus and unusual orchestration gives a special sense of color to the writing.”

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – tracks 1-10

The classic feature film overture“Opening Music, St. Petersburg” hearkens back to a lazy day aura from Mark Twain’s day with whimsical harmonica solos by Richard Hayman. The score goes on to highlight scenes with mood, emotion or augmenting action or the storyline. “Good Times by the River” melody flows like a raft upon lazy currents of the great river, past the landscape, the music encourages a moment to stare up at the sun or to the horizon beyond.

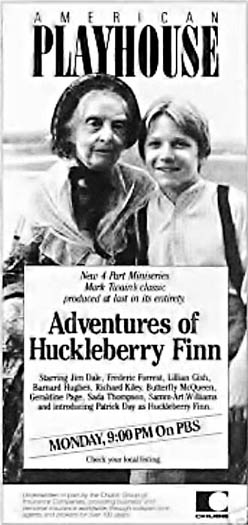

Lillian Gish and Patrick Day in an American Playhouse advertisement for Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

“Escape from Pap's Cabin” is filled with trepidation, curiosity and and a sense of the unexpected. Beats of a snare drum, with the melody escalating the scale and then descending, perilously swirls and whirlpools with strings and winds. Here, Perry's music does not rest, but moves on perpetually, escaping without pause. “Starting Downstream” has a strong feel of danger, adventurous while cautious, until the strings express "great relief" upon reaching the section of the river they know is the safety of home.

“The Raftsmen” restored scene opens with the folksy boing of a jewsharp, then bubbles jauntily into an upbeat harmonica melody and chorus. A rachet and pizzicato strings including String bass strike a happy harmony, and a shimmery tremolo is worked on the harmonica as the melody courses upward.

The “Arrival of Royalty” scene is marked first by substantial percussion, most notably kettle drums. The military edge of horns interplays with the vigorously tapped xylophone, the tune sprinting enthusiastically toward the last pomp of the circumstance of the royal arrival. “The Buggy Ride” soon strongly echoes portions of track 1 of Perry’s Jamestown Concerto in the background/incidental music; horn solos are joined by orchestra and a brief repose of French Horn solo. But soon the composition reins into a lively pizzicato-ing square dance style passage, and settles back down into the main melody. In the “Rescuing Jim” scene, Perry artfully wrings full emotion from the orchestra, again easing into primary melody while running the emotional distance from distraught tension to rescue's relief.

In disguise, Lillian Gish as Mrs. Loftus and Patrick Day as Huck Finn, with Lillian giving the lad pointers on how to act like a young lady.

”Closing Scene” brings back the lanquid strains of the harmonica, backed with orchestra harmonies. All is gaiety and replete with well-being; that balance of life and struggle and good times plays on in a setting of the distinctive South. The“End Credit Music” concludes the film with a more enthusiastic rendition of the main melody introduced in the opening music

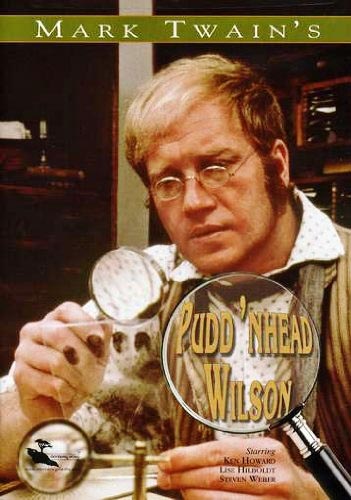

Pudd'nhead Wilson

DVD cover with Ken Howard as the title character, local lawyer Pudd'nhead Wilson

The "Roxy's Final Walk" scene has tender, devotional vocal chorals and the oboe d'amore pulling together all the emotions and feelings, while withstanding controversies and sad circumstances. Today we would term one of the themes in the film's storyline as "wrongful conviction."

The DVD is available on TCM and reviewer J.D. Hines rated the film as follows:

“Lïse Hilboldt steals the show as Roxie. Twain’s sensibilities shine through regarding race, injustice, and irony. Music done for closing credits is heavenly. Watch it, carnsarn you!”

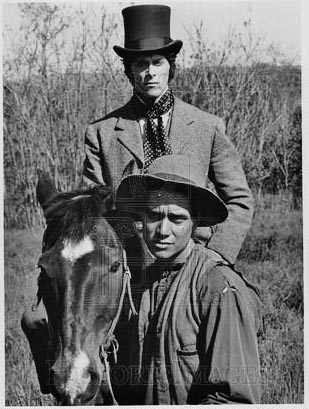

Steven Weber, later to star in the TV series Wings, and Preston Maybank portray master and slave in William Perry's production of Pudd'nhead Wilson broadcast on American Playhouse. The twist is that the identities of these two men were switched at birth. (Photo credit: Richard Howard)

Life on the Mississippi

This award-winning film was designated as one of the 10 best television films for 1980 by TV Guide. Robert Lansing portrayed experienced steamboat pilot Horace Bixby intent on teaching his apprentice "Sam Clemens" (David Knell) how to understand the means and the soul of the great Mississippi. The sweeping strings of "A Pilot on the Mississippi" and "The Romance of the River" with its wind solo perfectly reflect the ambiance of the mighty river's smooth flow and lazy riverboat traffic.

According to the IMDb, "The pleasure steamboat Julia Belle Swain of Peoria, Illinois was refitted to look like an 1850s riverboat to appear in the film."

Robert Lansing as a boat pilot and David Knell as his apprentice, Sam

For the scene "Courtship of Emmeline" a lightly waltzing orchestra serves up a romantic angle with glockenspiel accents and a satisfyingly sweet ending. "Disaster at Night" breaks abruptly from the romantic promenade to wake to military drumming and emotional strings and the shrill alert of horns. A sense of impending danger through a wind solo brings disaster closer into focus. "The Majestic Mississippi" scene melody, where before for "river music" it was often sweeping calmly, now the orchestra charges forth into vollies of regal phrases. Horns and strings clamber together with a French Horn solo as the orchestra builds in force to the conclusion.

The Innocents Abroad

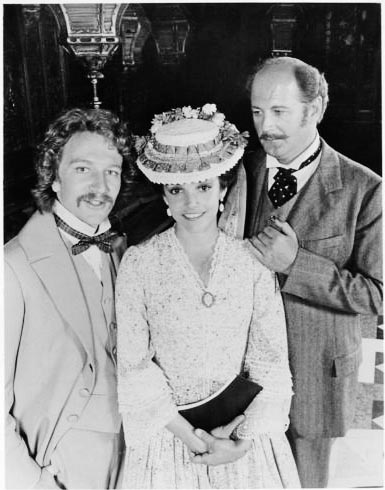

In the US (and Canada), the movie aired on Great Performances in May 1983. With the story’s itinerary, it was filmed on location in Egypt, France, Greece and Italy with the participation of numerous international production companies: William Perry's Great Amwell Company, KQED, the Nebraska Educational Television, Progéfi, TF1 and Taurus Film.

The score travels the world in style, and Perry devises a common theme that changes musical “flavour” for each destination – the bacarolle for Italy, a moody tarantella for Napoli, and an exotic processional for the camel caravan in Egypt. The story follows Mark Twain as he travels on a pleasure cruise from America to Europe and beyond. Twain even falls in love with “Julia” during the journey.

Scene music for “Mark Twain’s Theme” is jolly and sprite, featuring down home banjo strumming. In “Paris – The Can-Can,” with its interpretation of traditional can-can music, raucous horns, punching and rolling drums and percussion accompany the can-can kicks; frivolity and giddy fun with orchestra and kettle drum finishing off with a flourish. Perry's music in this movement possibly marks the first time a true Can-Can with full-scale orchestra has been written since French composer Jacques Offenbach’s 1858 “Galop Infernal” in Orpheus in the Underworld.

The strum of a mandolin is heard in “Gondolas in Venice” in a Bacarolle melody. The Italian vacation in “Genoa – The Bathtub Rag” has a slow ragtime dance with pizzicato strings, piano, drum kit and snare, with the snare drum pretty well mimicking a tap-dance in perfect time. “Julia” returns the quavering harmonica romantically to the background music.

Craig Wasson as Mark Twain, Brooke Adams as Julia Newell, and David Ogden Stiers as Doc on a pleasure cruise that takes them to points Europe and elsewhere. Barry Morse starred as the ship's captain.

“Welcome to Naples” is adventurously staccato, and the listener is treated to Italian street dancing and music. In “The Greek Chase,” the Greek folk dance is on, upbeat and lively, with plucky hints of Klezmer band music. An original touch is the brief banjo solo and other touches of banjo in the melody. “Egyptian Caravan” has a saxophone solo decorated with appropriate Middle-East oboes, and the music sways with the rhythmic pace of a desert camel laden with cargo. The “Closing Credits” has a patriotic intro followed by a harmonica vocal that merges into a full orchestra waltz, includes other musical phrases heard throughout the film, and it all merges into a great finish.

The Private History of a Campaign That Failed is a not too well-known Twain story. Its anti-war message regarding events in the Civil and Spanish-American Wars deals with the sad situation of a group of idealist boys who want to be soldiers and go to war. In their misdirected savage enthusiasm, they kill an innocent man. That farmer returns as a Godly messenger with a “War Prayer” aimed at a new generation of soldiers fighting in the Spanish-American War. Interestingly enough, Twain did not allow publication of the prayer in his lifetime.

The Private History of a Campaign That Failed (1981), VHS front cover

In “Girls Along the Road,” life is carefree, fun, reflected in the melody. War is then hinted at by miltary-ish notes from a muted trumpet, although the music carries on in an easygoing manner. “The Games of War/Lorena” startles with abundant opening strings rambunctiously having sheer fun. Perry incorporated the 19th century ballad Lorena which featured a delightful flügelhorn solo, the notes pure and smooth as though they had sandpapered edges. “Learning to Ride” is all frolicking fun and cracking the whip, as a French horn is accompanied by clippity-clop percussion. The “Title Music” ties the whole story together at the end with triumphant pizzaz and impelling solitary bell strikes. War is finally over!

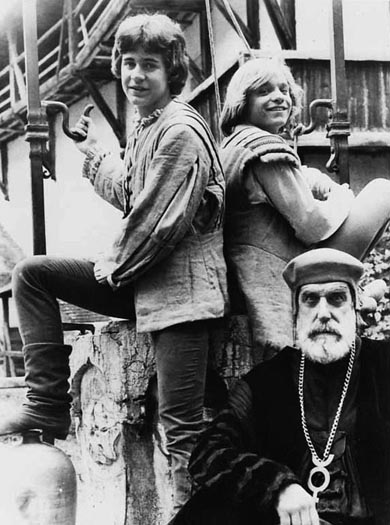

The Mysterious Stranger

Chris Makepeace, Lance Kerwin and Fred Gwynne in a publicity photo from The Mysterious Stranger, filmed in 1981.

The “River Scene and Main Titles” beginning overture is soft and dreamy enough to subtly slip the listener back in time, the overall melody drifting downward note by note through the scales. As the liner notes indicate, we are joining the music, and a printer's apprentice played by Chris Makepeace, as it becomes “a dream within a dream within a dream.” Perry conducted the Vienna Symphony and the Vienna Boys Choir for the 90 minute film, which follows the adventures of a printer’s apprentice from Missouri who daydreams himself back in time to a medieval castle and its problems in the early printing industry.

The overture effectively sets the stage for the next “acts.” In “44 in Fancy Dress” we are introduced to the magic-performing boy “44” (Lance Kerwin), who joins forces with Makepeace's character. The two boys, well, will be boys. 44’s magic also happens to be more powerful than the castle alchemist's (Fred Gwynne) The Vienna Boys Choir shines in their vocals, enhancing the mystical elements of the dream.

In “Fight of the Duplicates” they must also conquer a mutiny among the castle printers; this mutiny situation in the printing trade is something that Twain possibly encountered personally during the course of his career of having works published. The melody pursues the story, with the horns dominating the orchestra in a soon more sombre timbre. “The Burial of 44” is an orchestral dirge. A gentle choral passage, highlighted by a tender solo by one of the members of the Vienna Boy's Choir, gives a sense of realism to the dream.

For “Love Scene”, Perry, who has admitted he has a fondness for composing romantic themes, gives wings to this excerpt. The choir angelically rises toward visions, perhaps dreams of other visions. The melody then turns sharply off into a skirmish of dream against nightmare. As the liner notes suggest, “Therefore if one's life ever becomes difficult, one must “dream other dreams … better ones.” The gentle dreams, however, win the foray, and the melody resumes with sweetly soft vocals and orchestra, increasing in volume and intensity nearing the abrupt high note finale.

In “Closing Music” the opening drums, horn fanfare and strong chorals play like powerfully holding back the reins on fiery steeds. Then like a U-turn, wildness is gentled, and the main melody culminates with gentler chorals of the choir joining the orchestra. In the last minute the orchestra and choir elevate, with the power of grace, bestowing the melody with extraordinary grandeur, befitting the sweetest dream.

Mark Twain as a writer was pretty much the same in his approach. He could start out with a rough and common idea. He could catch the vernacular. Break a heart. Break down characters with fisticuffs or a browbeating. He built families and towns and sometimes whole universes into his stories, or at least he could transport your imagination to accept his other times and places. He did, at the very least, dream dreams within dreams....

Composer William Perry created the musical magic to spring these Twain stories from the page to the stage and screen, faithful in tone and time. Perry certainly had the feeling of knowing who Twain was and what he was all about, and it only seems natural that a little of Twain’s own magic beyond his words found its way into the composer’s music....